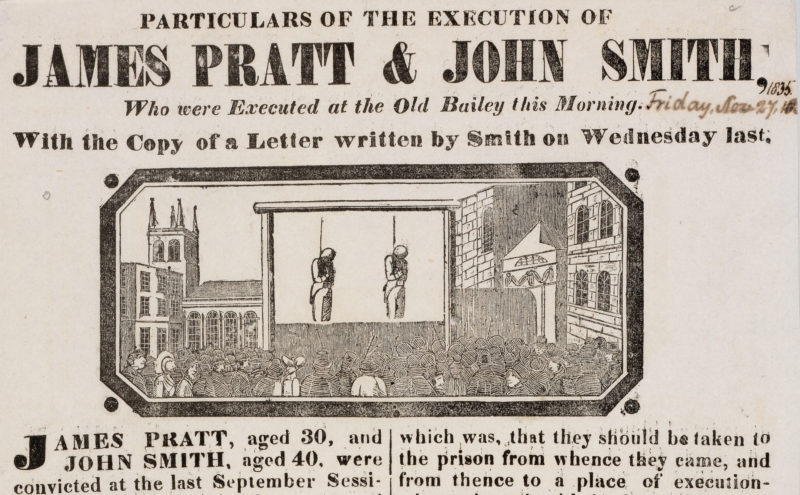

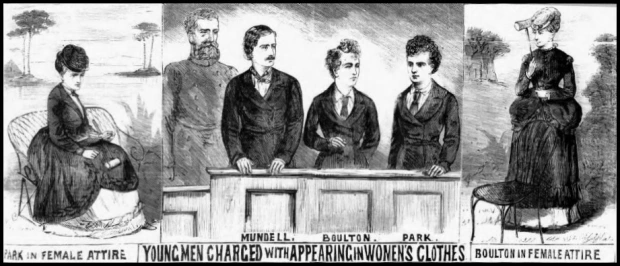

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people have faced legal proscription for hundreds of years, initially under religious laws, in particular those imposed by the Abrahamic faiths, and later under secular legal codes, often drawing heavily on the theological traditions that preceded them. Legal codes first implemented in Europe proliferated during the colonial period. As the European powers expanded their control and influence over much of the world, they took their legal systems and the laws criminalising LGBT people with them, imposing them over diverse indigenous traditions where same-sex activity and gender diversity did not always carry the same social or religious taboo.

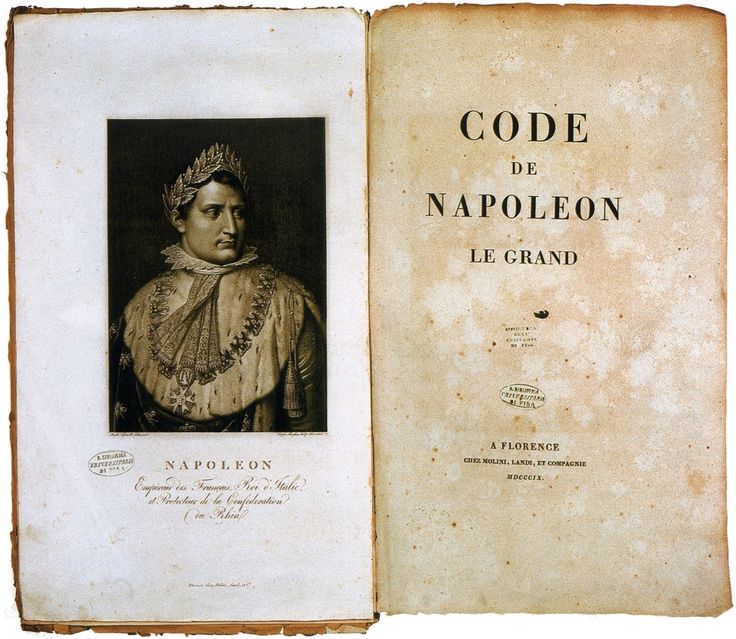

This timeline gives an overview of this history of the criminalisation of LGBT people, tracing in particular the evolution of the specific forms of criminalisation that originated in Europe and which are the source of many of the laws that still blight the lives of LGBT people across the world today. The legacy of British colonial-era penal codes looms large in this history, informing many of these criminalising provisions. Other colonial legal traditions, such as the French Penal Code (and later Napoleonic Code), which decriminalised same-sex sexual activity in 1791, did not have the same long-lasting effect on the lives of LGBT people. Other traditions of criminalisation or censure, particularly those heavily influenced by Islam and other religions, are not interrogated in detail here.

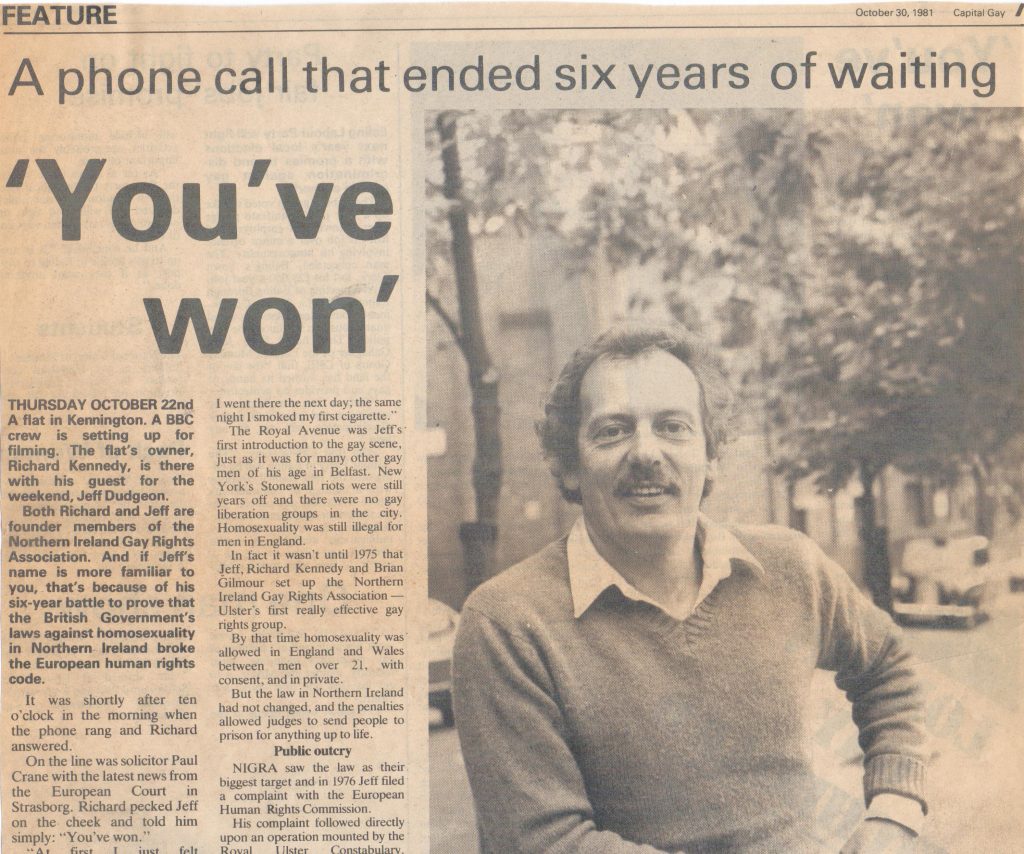

The timeline also follows how this legacy of criminalisation has increasingly been undone, highlighting important milestones in the global, century-long struggle to achieve justice and equality before the law for LGBT people. While the fight for LGBT equality is far from complete, the distance travelled, even in the last 50 years, is reason to be hopeful. Despite the long history of the criminalisation of LGBT people, the long arc of history bends inexorably toward justice.