Around a third of countries in the world explicitly criminalise LGBT people in some form. While this achieved in a variety of ways, and enforced to varying degrees, wherever these laws exist they have a profoundly negative effect on the LGBT community.

How are LGBT people criminalised?

Laws which criminalise LGBT people are invariably framed in a way which criminalises sexual acts rather than identities. The specific framing of criminalising provisions varies from country to country, though common formulations include ‘sodomy’, ‘buggery’, ‘indecency’, ‘unnatural acts’, ‘homosexuality’, ‘lesbianism’, and ‘cross-dressing’.

In many cases, criminalising provisions are vaguely worded and unclear in scope, allowing a large margin of interpretation by law enforcement officers and judges, who are enabled to introduce their own prejudices when enforcing the law. Additionally, the existence of these provisions encourages police officers to act beyond the exact letter of the law, and arrest, charge, and prosecute people based upon their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity even where no prohibited act has been committed or can be proven.

In some countries, law enforcement officers also arbitrarily apply other criminal provisions, such as ‘public nuisance’, ‘public order’, and ‘vagrancy’ laws, to arrest and detain LGBT people.

While there have been attempts to expand criminalisation to include merely identifying as LGBT, such as a bill under review in Ghana , these have as yet failed to materialise.

Who is criminalised?

Of the 65 countries which currently expressly criminalise same-sex sexual activity, all of them criminalise intimacy between males. 41 criminalise intimacy between females, either through gender-neutral provisions, or provisions which expressly cover female sexual activity.

The reason for this discrepancy is not due to any higher degree of acceptance of same-sex relationships between women, but rather a misguided belief that such relationships did not exist at the time these laws were created. This was evident in Britain when a 1912 attempt to expand ‘indecency’ laws to sexual acts between women was shelved in part due to a claimed lack of evidence that such acts were sufficiently widespread.

Nevertheless, a number of countries have opted to expand their criminalising provisions to include acts between women in recent decades, with Trinidad and Tobago beginning a trend in 1986 which saw at least ten countries criminalise LBQ women for the first time. See A History of LGBT Criminalisation for a detailed timeline of the expansion of criminalising provisions to women.

Read more about the criminalisation of sexual activity between women in our report, Breaking the Silence: Criminalisation of Lesbian and Bisexual Women and its Impacts.

Transgender and gender diverse people are another group targeted by laws criminalising LGBT people. At least 13 jurisdictions maintain laws which explicitly criminalise people whose gender expression doesn’t align with their sex assigned at birth. This is most commonly achieved through ‘cross-dressing’ laws, though provisions criminalising ‘impersonation’ and ‘disguise’ also exist, and are used to target, harass, arrest and prosecute trans people.

Read more about the criminalisation of transgender and gender diverse people in our report, Injustice Exposed: The Criminalisation of Transgender People and its Impacts.

Furthermore, a number of countries which have decriminalised consensual activity between adults of the same sex nonetheless maintain discriminatory ages of consent between opposite and same-sex intimacy. In effect, this means that young LGBT people can be liable to criminal prosecution for acts which their heterosexual peers can lawfully engage in.

Where are LGBT people criminalised?

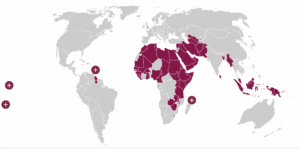

LGBT people are criminalised in most regions of the world. This includes:

- Africa – 31 countries criminalise LGBT people in some form, the most of any region.

- Americas – 5 countries, all Caribbean, criminalise sexual activity between people of the same sex.

- Asia – 23 countries criminalise LGBT people, the majority of which are in the Middle East.

- Pacific – 6 countries criminalise consensual same-sex sexual activity.

For a detailed breakdown of the countries that criminalise LGBT people, see our Map of Criminalisation.

Where did these laws originate?

While LGBT people have faced legal proscription for centuries, laws which explicitly criminalised LGBT people proliferated during the colonial period, as European states expanded their control over large parts of the world, exporting their discriminatory criminal laws in the process.

British law is by some way the largest source of criminalisation. The country was prolific in spreading provisions criminalising same-sex sexual activity to its colonies. More than half of countries which criminalise LGBT people today can trace the source of their law to Britain, either as a former colony or ‘protectorate’, or another historical relationship. Provisions include ‘buggery’, ‘unnatural offences’, and ‘indecency’, while ‘cross-dressing’ and other laws criminalising gender expression also largely find their origins in British colonial law.

Not only did Britain export laws criminalising LGBT people, but the broader sexual offence regime imposed on colonised states was, and continues to be, discriminatory against other marginalised groups including women, children, and people with disabilities. The Human Dignity Trust has undertaken detailed research examining these Commonwealth laws which continue to exist today, including through a series of reports and an online digital tool.

Other colonial powers such as France and Spain, whose legal systems were heavily influenced by the Napoleonic code which did not criminalise same-sex sexual activity, did not have such a lasting impact in terms of anti-LGBT laws.

Another significant source of criminalisation is Islamic law. Several countries which criminalise LGBT people today do so not through inherited colonial law, but from a strict interpretation of Sharia law. While less prevalent, the penalties available tend to be more severe, with the death penalty imposed or at least a legal possibility in 11 Muslim-majority countries.

For a detailed exploration of the proliferation of anti-LGBT laws, see A History of LGBT Criminalisation.

What punishments are imposed?

A range of sentences are imposed under laws that criminalise same-sex sexual activity. With the exception of Eswatini and Namibia, where the sentences available are unknown, the maximum prison sentences available, with or without fines, are as follows:

- Up to one year imprisonment – 5 countries

- Two to four years’ imprisonment – 13 countries

- Five to nine years’ imprisonment – 11 countries

- Ten to 19 years’ imprisonment – 14 countries

- 20 years’ imprisonment – 1 country

- Life imprisonment – 8 countries

- Death penalty – 12 countries

The sentences imposed in the 13 countries which maintain laws criminalising gender expression also vary. The maximum sentences available, with the exclusion of Indonesia, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia, in which the sentence imposed is unclear, the maximum prison sentences, with or without fines, are as follows:

- Less than one year imprisonment – 6 countries

- One year imprisonment – 3 countries

- Two to five years’ imprisonment – 3 countries

What are the impacts of criminalisation?

Criminalisation has a number of damaging effects on LGBT people. Most obviously, criminalisation means that LGBT people can be lawfully arrested, detained, and prosecuted simply for being who they are. When in detention LGBT people are vulnerable to further abuses, including verbal harassment, physical assault, sexual violence, and the denial of healthcare and legal representation. Countless examples of torture and other types of ill-treatment of detained LGBT people in criminalising countries have been documented.

Even where laws are not enforced, the mere existence of these provisions has deeply harmful effects on LGBT people. Criminalising provisions are used both by law enforcement and the public to harass, threaten, and extort LGBT people. Their existence perpetuates stigma and prejudice, providing tacit approval of discrimination and violence against LGBT people. Under these legal regimes LGBT people are excluded from society, and feel unable to report crimes for fear of abuse and arrest by police officers. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the laws won’t be enforced in future.

International human rights mechanisms, including the UN Independent Expert on SOGI and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, have called for these laws to be repealed due to their pervasive negative impacts.

We have published detailed reports examining the specific impacts of criminalisation on both lesbian and bisexual women and transgender and gender diverse people.

What are the human rights implications of criminalisation?

Criminalisation is in clear breach of international human rights law. LGBT people have increasingly been recognised as a protected group under non-discrimination provisions. Criminalisation not only violates the right to non-discrimination of LGBT people, but other fundamental rights such as the rights to privacy, legal recognition, humane treatment, expression, association, and assembly, among many others.

A number of international human rights bodies have issued rulings recognising that the criminalisation of same-sex sexual activity violates the rights of LGBT people. This includes the European Court of Human Rights (Dudgeon v United Kingdom,1981), the UN Human Rights Committee (Toonen v Australia, 1994), the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Henry and Edwards v Jamaica, 2019), and the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (Flamer-Caldera v Sri Lanka, 2022).

Furthermore, cases such as Goodwin v United Kingdom (2002) at the European Court of Human Rights demonstrate that states must equally protect the rights of transgender and gender diverse people, and ensure non-discrimination under the law.

For a detailed explanation of state obligations related to sexual orientation and gender identity under international law, see the Yogyakarta Principles.

How can criminalisation be addressed?

There is a clear trend towards decriminalisation of same-sex intimacy in recent decades. Almost 50 countries have decriminalised since the beginning of the 1990s, with many more having done so earlier in the twentieth century, while some countries have never criminalised same-sex sexual activity in their history.

A majority of countries achieve decriminalisation through legislative reform, with governments actively taking steps to repeal discriminatory laws or opting not to include criminalising provisions in new criminal legislation. A smaller number of countries have achieved decriminalisation through litigation, with successful legal challenges leading courts to declare criminalising provisions unlawful.

However decriminalisation is achieved, the persistent and tireless advocacy of LGBT organisations and activists is essential. Their commitment to overturn discriminatory laws has seen the tally of criminalising countries gradually fall. While there is still much more work to do, there is reason to be hopeful that these laws will eventually be eradicated.

The Human Dignity Trust supports civil society organisations and activists in their challenges to criminalising provisions in the courts, as well as supporting receptive governments to enact legal change through legislative reform. Read more about our support for litigation and legislation reform work.